The Only Kind of Patriotism Worth Having

We keep arguing about who’s a “real” American while the server’s crashing. Reboot first, identity quiz later.

Being a patriot in Donald Trump’s America is like sitting through the trial of a beloved relative for a grisly crime - still showing up, still hoping for exonerating evidence, and slowly realising you’ve become the person who says “Let’s hear the chainsaw out” before judging. You keep waving across the aisle, trying to believe your country is more than its worst headline and that democracy is more than a themed escape room with no exits.

We’ve always squabbled over what patriotism even is. Tocqueville, France’s most observant Airbnb guest, offered two models. First, the instinctive kind: hearth, soil, surname, cemetery plot. (Warm. Smells like gravy.) Second, the reflective kind: laws, rights, consent of the governed. (Cool. Smells like library.) America, characteristically, tried to juggle both and wound up flinging gravy around the reading room.

Today, both versions have curdled. Instinctive patriotism has been repackaged as a blood-and-soil membership scheme - real Americans on one side, everyone else on a waiting list that never clears. Reflective patriotism, over-schooled and under-lived, risks turning into a posture: the flag as text, the anthem as problematic soundscape, citizenship as a peer-reviewed thought experiment. One side hugs the country so hard it can’t breathe; the other folds its arms and asks for citations.

Neither produces citizens. The first crowdsurfs toward a strongman. The second retreats into immaculate critique - great thread, zero plumbing fixed. Tocqueville would recognise both and, in that courteous Old World way, suggest we stop being ridiculous.

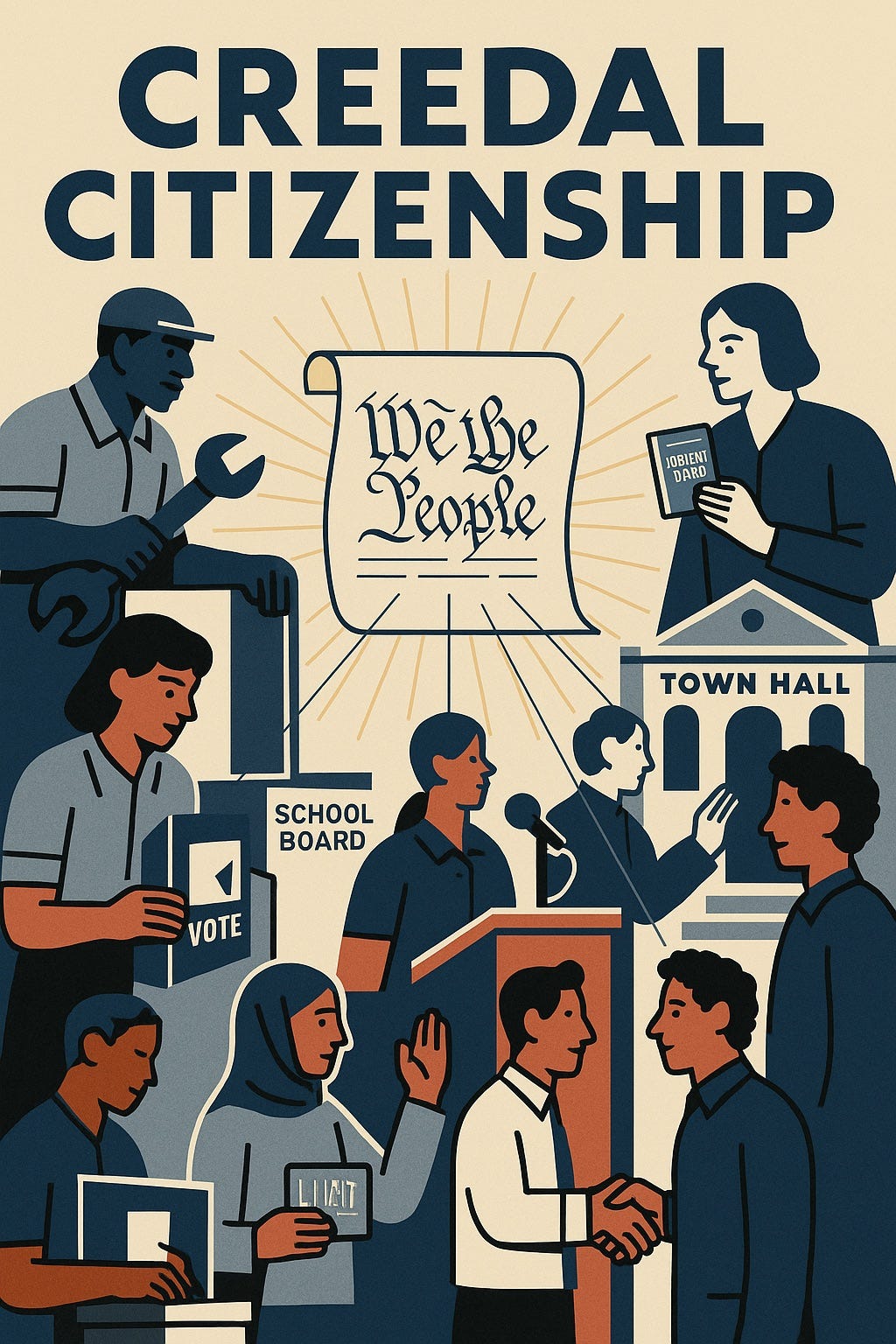

Lincoln did more than suggest. In the 1850s he argued that the Declaration contains an “electric cord” binding anyone who chooses its truths: that all people are created equal, and that government derives its just powers from consent. Belonging, he said, is adoption, not ancestry. You don’t need a relative at Shiloh; you need to act as if equality and self-rule are real obligations, not wall art. That’s the only patriotism worth having: creedal citizenship.

It isn’t cute. It’s a discipline. A creedal nation can absorb newcomers, dissenters, sceptics and those uniquely American life forms who correct your grammar during a house fire. It gives us a language: liberty, equality, self-government and a to-do list. It doesn’t demand unanimity; it demands we show up on Tuesday night when the agenda item is “Bus Routes (2 of 7).” If your politics never require a bad folding chair, you’re not doing citizenship; you’re doing content.

Why is creedal patriotism unfashionable? Because it is work, and sincerity is embarrassing. It asks us to defend ideals our institutions routinely betray, earnestness that risks looking like cosplay. It asks us to share a political home with people we find unbearable - neighbours who salt their chips wrong and vote worse. Worst of all, it asks us to judgeour own side by the standards we preach at theirs . Easier alternatives beckon: country as team jersey (shout louder), or country as case study (shrug harder). Neither requires you to get rain on your coat.

When we drift, history clobbers us with reruns. The Know-Nothings, the 1920s quotas, the masked theatrics - always sold as patriotism, always ending in exclusion. The more we define Americanness by soil and blood, the smaller “us” becomes until - miracle! - it fits precisely around whoever’s holding the microphone. Flip side: refined despair. America as marketing plan. Beautiful theory; shame about the species. Follow it to the end of the corridor and you’ll find a locked door labelled “Nothing To Be Done,” plus a seminar evaluating the typography.

There is something to be done. In democracies, patriotism becomes a habit before it becomes a feeling. Tocqueville again: devotion strengthened by ritual. Not the fireworks and bunting (enjoy them; don’t mistake them). The rituals are mundane: jury service without Broadway-level excuses; local elections that sound like budget meetings because, tragically, they are; reading the agenda; serving on the board you’ve been doomposting about; sponsoring newcomers into your neighbourhood instead of applauding them from a tasteful distance; speaking to opponents as if you intend to share a country tomorrow and the next day and, yes, after the election too.

If that feels small next to the baroque awfulness of the news, that’s the point. The American creed is not just a founding flourish; it’s a method. It assumes ordinary people, given equal dignity and fair rules, can govern themselves tolerably well. (“Tolerably well” is the operative phrase. We are not Switzerland; we are jazz.) It assumes we will argue, count, lose, and try again. It is humble about human virtue and audacious about what citizens can build. It’s the only patriotism that doesn’t require a lie.

It also insists on hope with a memory. Not frothy optimism; stubborn recall. We’ve been better; we can be better; and mortifyingly, we are the ones who must do it. Hypocrisy doesn’t cancel the creed; it energises it. We measure ourselves against what we say we are, we see the gap, and we work. The alternative is to lower the standard until we can declare victory in a country no longer worth winning.

“Yes, but look around,” you say. “Institutions cracking, norms shrugged off, corruption buzzing like a faulty streetlamp.” True. The temptations are familiar. One: hand the keys to a strongman who promises to tidy up (spoiler, you’re what gets tidied). Two: declare the house uninhabitable and move into moral exile (excellent acoustics, zero plumbing). The creedal option is grimmer and more adult: fix the house while living in it with neighbours you did not audition.

So what does practising this look like?

Less performance, more service. You cannot volunteer your way out of every crisis, but you can join the committee that prevents three dumb ones.

Fewer purity tests, more coalitions. If everyone at your meeting agrees with you, you’re in a brand exercise, not a republic.

Less talk of “real Americans,” more insistence on equal Americans. If the adjective is required, the noun is in danger.

Fewer doom-scroll catechisms, more actual democracy. Petition, assemble, vote, serve. Post if you must—after.

The reward is not a spotless conscience or a perfect country. It’s steadier: the right to love a place you are actively building. It’s the ability to look that metaphorical defendant in the eye and say, “I’m here because we can be better, and because I’m responsible for my share.” It’s the knowledge that, between the cynical shrug and the clenched fist, there remains an open hand.

Let’s also be honest about tone. Authoritarians hate laughter because it betrays fearlessness; cynics love it because it absolves them of effort. The trick is to laugh and turn up on Tuesday. Smirk in one hand, clipboard in the other. It’s very unfashionable. It also works.

If love of country means blind loyalty to a leader, tribe, or myth, it ends - as always - in repression marketed as renewal. If love of country means permanent disdain until conditions meet your boutique standards, it ends—as always—in elegant withdrawal. Creedal patriotism is the messy middle: loyalty to strangers because they are citizens; loyalty to institutions because they are the tools we have; loyalty to ideals because without them we are just resentments with postcodes.

So: fewer selfies with the Constitution, more reading of it. Fewer sermons about decline, more line items about buses. Less “Only real Americans…” and more “All equal Americans…” Less cosplay of 1776, more practice of 2025.

And when the next grim headline lands, and it will, don’t choose between the team jersey and the case study. Choose the folding chair. Choose the vote you might lose and the meeting you’d rather skip. Choose the unglamorous rituals that keep the electric cord humming. That’s the nation. That’s the work. Roll up your sleeves.

(And if you need a slogan: America - some assembly required. Bring tools. No algorithm will do it for us.)