What’s in a bubble? And is AI an innovation made out of soap?

Throughout history, markets swell and burst like overripe balloons. From the South Sea fiasco to 17th-century tulip mania, bubbles have stamped themselves onto economies and memory alike.

Today, with everyone whispering about an “AI Bubble,” we have to ask: breakthrough, hype cycle - or both?

A Brief History of Bubbles

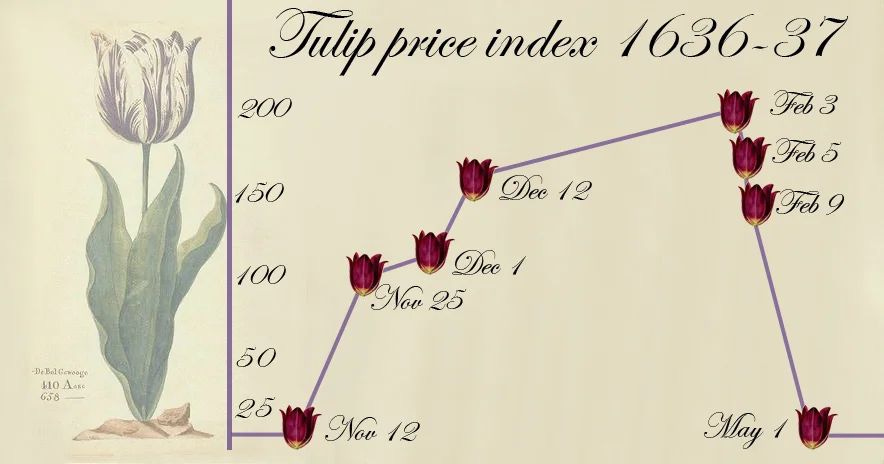

The first widely cited bubble, the Dutch Tulip Bubble of the 1630s, saw bulbs trade at house-level prices - florals as blue-chip as it gets. Then 1720’s South Sea Bubble sent shares skyward on fantasies of South American trade that turned out to be, well, imaginary.

Fast-forward: the 20th century served up the biggest pop of all - the Great Depression. The Roaring ’20s ran on easy credit, surging profits, and Europe’s post-WWI rebuild. A decade on, demand faded as Europe reindustrialized, undercutting U.S. suppliers.

And pop! Black Thursday, October 24th 1929, the panic selling began and splat the market crashed right into the Great Depression. On the bright side it inspired some great literature - The Great Gatsby comes to mind. But also maybe WWII, so not so great... Dangerous things these bubbles.

The Irrational Exuberance of Financial Bubbles in the Modern Era

It was 1996 and none other then the redoubtable, irreproachable Alan Greenspan warned - “How do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset value ...”. There we were right dab in the middle of the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s. We were feeling good. You know it was while company values were rising and investing in them felt inevitable, obvious, necessary. Netscape started it in 1995 with a share price in first day of trading that went from $28 to $58.25 by the end of the first day. E-trade followed in 1996 along with Amazon in 1997 with a share price that climbed 30% its first day of trading.

1998, Ebay IPO’d at $18 ending at $53 on the first day. But for all the Blackberry’s or Broadcoms there were also Globe.com’s. Companies with little more than a flashy website saw their stock prices soar into the stratosphere. Investors were entranced by promises of internet riches, throwing caution to the wind as they poured money into businesses that had little more than a good url and the best graphics CSS2 could provide.

When the bubble burst in 2001, many lost their shirts. At least a few folks were left with a snazzy collection of digital beanie babies though.

The pattern is instructive. In the late ’90s, internet firms soaked up ~39% of total investment; 1999–2000 IPOs were overwhelmingly dot-coms. M&A went manic: Yahoo bought broadcast.com for $5.7B; AOL–Time Warner (2000) stamped a $167B ticket and wrote down $100B by 2002. Pop. Yet the rubble hid tomorrow’s giants: Amazon, PayPal, eBay, Google - alongside stalwarts Apple and Microsoft - compounded for decades after the purge.

And Now, the AI Bubble?

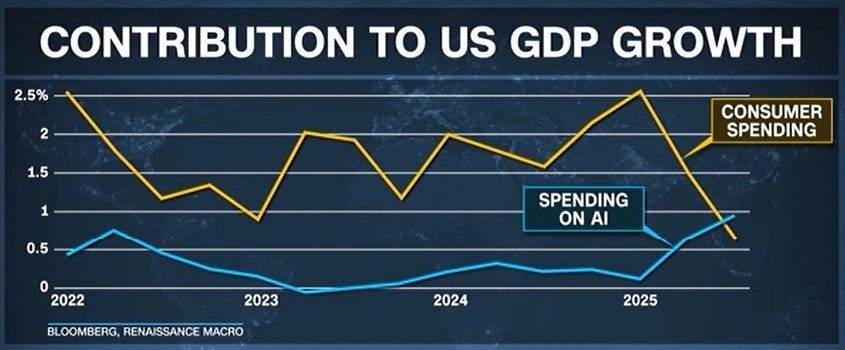

Cue present day: AI jargon, machine learning, deep learning, LLMs, agents, “experience compression” falls like wedding confetti. Giants and startups alike are racing to capture the prize, and investors are obliging. In Q3 2025, ~40% of investments reportedly flowed into AI; Anthropic alone raised $13B (roughly 15% of that pie). Economists credit over half of the U.S.’s 1.8% GDP growth to AI. Some see the birth of the next great bubble; others see the scaffolding of the next platform shift. A few companies, OpenAI, Anthropic, xAI, look positioned like Amazon/Google circa 1999.

But let’s not pretend everything is bulletproof. If half of GDP growth is just AI investment, that’s concentration, not diversification. Many AI players are still running the growth-over-profit playbook of the 2010s. Total AI revenues haven’t cracked $100 B, far from breakeven, and a long way from JPMorgan’s $650B revenue threshold they estimate would justify current capital flows.

There’s a running joke that OpenAI, Anthropic & co. built the world’s most sophisticated homework helper. And sure, when school let out this summer, usage took a sun-soaked 70% nap. You could read that as “uh-oh,” or simply as seasonality from the most AI-native users not being in the workforce yet.

In other words: less “existential risk,” more “summer break effect.”

The real test comes as these users graduate from homework to workflows, the same “cheating machine” becomes a Swiss-army knife for briefs, decks, tickets, and tickets about decks.

And If It’s a Bubble?

If AI turns out to be a bubble, it won’t just rhyme with dot-com - it’ll audition for a bigger tragedy. Western economies are still wobbling on post-pandemic legs; headlines insist everything’s fine while wallets file dissenting opinions. Energy bills? Up. One culprit? Hyper-hungry data centres chewing kilowatts like popcorn to keep the chatty machines chatting. If that froth pops, we’ll have spent a chunk of the recovery building a growth gizmo that doubles as a self-eating energy monster. Great for GPU vendors, less great for anyone buying groceries.

And yet, bubbles have a rude habit of leaving useful stuff behind.

The web cratered in 2000; a decade later we were all carrying tiny dot-com dispensers we poked at 60% of the day. AI already trims meetings, drafts, and drudgery, even if it also hallucinates your job title. So yes, a bust could torch growth in the short run; the survivors could still mature into the next Amazon or Google over the long slog. Worst case, by 2030 we’ll be bailing out chatbots that are “too loud to fail,” and they’ll promise to be good this time if we just upgrade their power supply.

As ever: “Conventional beliefs only ever come to appear arbitrary and wrong in retrospect; whenever one collapses, we call the old belief a bubble.” — Peter Thiel

Keep up to date with The Letts Journal’s latest news stories and posts at our website and on twitter.